The Anxi county and its Tieguanyin

January 9, 2015

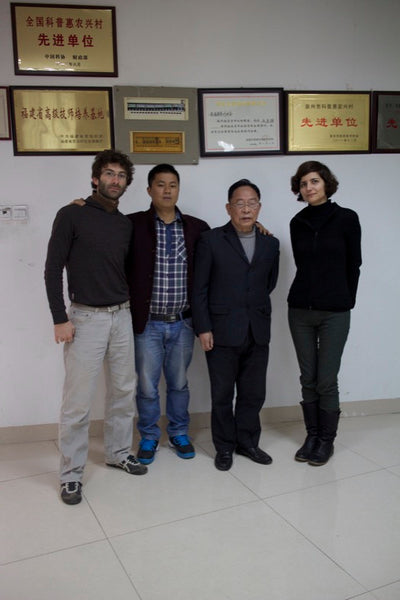

After a quick breakfast in the car, we go to the offices of the Anxi Tea Society. Together with Michela and myself there are W.W., his chubby friend P.Y. and a lady -W.W.’s classmate in primary school. They all took two days off to come with us. P.Y. is also in the tea business. He owns 1/3 of a company selling tea on Taobao, the Chinese Ebay. 20 employs manage the orders from the offices in Anxi city, where the tea is also packed and store. He will be our driver through the county.

We drink tea with the vicepresident of the Tea Society while waiting for Li Zongyuan.

Li Zongyuan is a famous expert of Anxi Tieguanyin. Born in 1942, he dedicated all his life to Tieguanyin. He studied at a professional tea school, wrote books and published papers in 17 tea journals. In 2002 he became a certified senior tea taster; among the first four persons to receive this title. After retirement, he was elected senior agronomist professor and nowadays is still active as a tea consultant.

Unfortunately, he doesn’t speak a word of English. He shakes our hands, gives us his business card and takes a sit in front of us. After a short discussion with our friends he starts speaking holding an undisturbed, 10 minutes long monologue. We record his words for later translation.

There is time only for two questions. We ask which is the best tieguanyin harvest season, spring or autumn? He replies autumn, without giving further explanation. We heard the same answer yesterday evening. We are a bit puzzled, since we were always told that the spring harvest is the most floral and expensive one.

The answer to the second question is also unexpected: “Is pure tea, from a single crop, better than blends?” The answer is negative. For Li Zongyuan the tea master is an artist, who blends different leaves together to conceive a supreme tea. This year we have already heard this opinion; however, to our previous knowledge, blending is used for tieguanyin to keep a consistent taste profile over the years, rather than to produce better tea. Contradictory opinions in the tea field are common, to remind us that we will never grasp it all. At the end, tea is not an exact science and its complexity is part of his charm.

Lunchtime. Today seafood. In the restaurant hall we choose the living fishes from aquariums. Among them also a strange animal, never seen before: a horseshoe crab. Often referred to as living fossils, the horseshoe crab has changed little in the last 450 million years.

After lunch we drive to Xiping. In every direction we see lines of small tea bushes growing on an arid, reddish ground; the color is given by the high iron content. It must be back breaking to stay bent down on these little bushes to pick the leaves. For best results, 2-3 years old trees should be used to produce Tieguanyin. Usually the plants are anyway replaced every 8 years.

After one-hour drive we stop to visit a memorial near Xiping. The monument is dedicated to Shirang Wang who, according to tradition, was the first to bring Tieguanyin to the emperor Qianlong back in the Qing dynasty.

After a tea offered by the memorial’s attendant we drive for additional 30 minutes to a small village in the countryside. The landscape is beautiful. A warm and relaxing light at sunset colors the traditional house roofs and the hills surrounding the village.

Tonight we will sleep by a friend of our guide whose family live out of Tieguanyin production (photo above). To honor the foreign guests the father killed a chicken, which was served us for dinner filled with clams and feet included. At night the temperature drops close to the freezing point, both outside and inside. Drafts pass through the windows, and some are even missing altogether (the house is under renovation). We freeze, but our guests are impassive. They wear the same cloths at day, at 20°C under the sun, and at night.

Our host takes some Mao Cha out of the fridge, remove the stems (see photo below), and prepare tea for us until it’s time to go to bed. Mao Cha is the name of every tea not yet completely processed. In the case of Tieguanyin, the stems attached to the leaves shall be removed by hand as a last production step.

January 10, 2015

Breakfast with porridge and stewed celery with tofu. A short visit in the court of a traditional house and again in the car for a 1.5 hour drive to Longjuan.

Here we visit an organic Tieguanyin factory. The tea plants are right in front of the factory. Everything is clean and tidy. After a walk through the tea gardens we move inside to see the machinery for leaves processing and taste tea. We drink several Tieguanyin, both green and roasted. Michela and I share the same opinion: all teas are shy, missing strength and savor. We drive back to Anxi city and stop at the teashop of the factory: maybe all good tea was already sold to the shops. We try again the tea but the taste is the same. A pity! It was a challenge for our guide to find organic Tieguanyin (we explicitly asked for it) and everything looked perfect at the factory. Just the most important aspect, the tea, was not worth buying.

The last picture above shows a low-fire and a middle-fire tieguanyin -left and right, respectively. Nowadays the low-fire is by far the most common. The leaves are greenish, fresh and floral. It is more indicated for hot-body persons. To taste the middle-fire tea we shall always explicitly ask for it. More brown in color, this tea is less floral and warmer. Top quality feature a sweet and lingering aftertaste. There is also a third, high-fire version, much less common. The taste is very intense and strong. It reminds me a heavily roasted Yan Cha (Wuyi Rock tea) rather than a tieguanyin. Middle- and high-fire versions are the traditional tieguanyin teas. The low-fire tea was recently introduced in the market and gained quickly popularity due to the intense floral notes.

Our time in Anxi is over. In the evening we take a bus back to Fuzhou and tomorrow morning we will head north. I will travel back to Shanghai while Michela will venture to Longquan, where the world’s famous Celadon pottery is produced. The city is small and it will be not easy to find a reliable guide. Michela feels excided and frightened at the same time. She will report her trip in Longquan in the next blog entry.

In the picture below:

- Tea bag machine in a small shop near Longquan: low-quality tea is reduced in powder and sealed in tea bags.

- Temporary workers remove stems from Mao Cha in a shop in Anxi city.